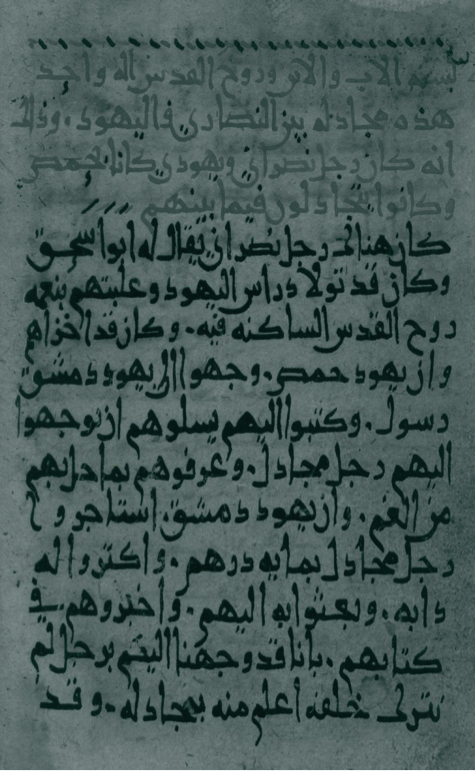

A Disputation in Ḥoms between Abū Isḥāq the Christian and the Jewish Debater from Damascus

The long-standing Christian tradition of casting refutations of Judaism in the form of Jewish-Christian disputations was continued by Arabic-speaking Christians in the Muslim world. Among the many Christian Arabic Adversus Judaeos texts, of which the JewsEast team is aiming to create an exhaustive survey, there is a curious example of a text which goes under the simple title ‘The Disputation between the Christians and the Jews’ (Mujādala bayna l-Naṣārā wa-l-Yahūd).

It survives in two manuscripts, of which only one is currently accessible: MS Milan – Biblioteca Ambrosiana X201 sup, fols 214v-227r. Although the manuscripts are about two centuries younger, it can be assumed that the text was written in the early ninth century, on the basis of the two eminent Muslims mentioned in the text.

Setting

The text features a skilled Christian debater (mujādil), Abū Isḥāq, who is challenged by the Jews of Homs in a discussion about religion. The Jews of Homs had made the mistake of engaging Abū Isḥāq in debate before and they had done miserably. Now they decide to outsmart Abū Isḥāq by hiring the most brilliant Jewish debater from Damascus, paying him ten dinars and sending him a riding animal. He puts a condition however: the person who will end up losing the debate will have to wear a halter and a saddle pack and be ridden around all the markets and alleys of Homs with a young man of his religion on his back. The Muslim notable Junāda ibn Marwān contacted Abū Isḥāq to invite him to the disputation and oversaw the signing of this condition to the dispute. He also made his brother, the judge ʿAbd Allāh ibn Marwān, the arbiter.

Abū Isḥāq and the Jew agree that the Jew may begin asking a question. He asks Abū Isḥāq whether he can agree with him that God has always shown special support for the Jews and he wants to prove this by asking him seven subquestions. Each of these questions revolves around miraculous aspects during the Exodus and the way these reveal God’s special favour of the Jews: the delivery from slavery in Egypt, the gift of clothes and jewelry to the Jews, the destruction of the Pharao’s army, the manna and the quails etc.

Abū Isḥāq’s strategy soon becomes clear. He replies to every point but turns the interpretation of every miraculous event upside down. Rather than seeing the Israelites’ delivery from slavery as a positive point, he argues that God simply kept his promise to Abraham and that 430 years of slavery is hardly a sign of Divine support. The Jew’s argument that God destroyed the armies of the Pharao because He wanted to protect and reward the Israelites is countered by the argument that God merely wanted to punish the Egyptians for their polytheism.

In this way Abū Isḥāq undercuts the Exodus as the founding myth of the Jews. In some cases the Jewish argument about the Exodus seems to have been formulated to let Abū Isḥāq score easily, for example when the Jewish debater highlights God’s special gift to the Jews consisting of shoes and clothes that did not wear out during all the years the Jews wandered in the desert (Deut 8:4 and Deut 29:5). Abū Isḥāq retorts [fols 223v-224r]: ‘Don’t you know that a man is happy when he changes his clothes!? And you spent forty years in a dirty shirt, with your lice and your filth. You slept in it and got up in it and you had intercourse with your wives in it. In it you smelled like the grave, because there was quail blood and fat in it and the stench of manna, and you did not have soap to wash your clothes with!’

In the guise of ‘argumentation’, the Christian debater paints a humiliating image of the Jews. By phrasing the passage in the second person plural he points his finger not only at the Jews during the Exodus, but also to the contemporary Jews, who – he claims – are known for their dirty and low-status professions.

For the modern reader it may be tempting to conclude that such a negative caricature is mostly meant for internal consumption among Christian readers, whose sense of community and superiority would be reinforced by the humiliation of the Jews. The possibility such statements would be written down to serve as models of how to debate with Jews seems less likely, especially in the early ʿAbbasid period when rational argumentation was held in much higher esteem.

Interestingly though, there is a popular Jewish text from roughly the same time that ridicules Christianity in the sharpest possible way and uses the same tone. This is the so-called Qiṣṣat Mujādalat al-Usquf, the 'Story of the Disputation of the Bishop'. While most of the text consists of critique of the Christian religion in the form of satire mixed with dilemmatic questions meant to constrain the Christians to admit the irrationality of their beliefs, there are also some of proofs of the superiority of the miracles of Moses over those of Christ:

‘Most wondrous of all, he transformed his staff into a snake, and [...] he split the sea into twelve roads and Pharao and his people, horses and soldiers were drowned […] He gave them His Law on Mount Sinai. He brought down for them the manna and the quails. He made springs of water gush from the rocks for them. He led them through the wilderness, their clothes did not become tattered nor did they go barefoot. Furthermore, as a punishment to Korah, and his people, the earth opened up, it swallowed them alive, and they perished. This is more wondrous than what Christ did. You must then worship Moses, peace be upon him, because he is greater than Christ.’ [Stroumsa, Lasker 55-56]]

Although there may not be a direct connection between this anti-Christian text and the Disputation of Abū Isḥāq, they were probably both written in the early ninth-century. The specific mentioning of the clothing that miraculously did not wear out may point to this element of the Exodus featuring in real exchanges between members of the two religions.