A Monastic Genealogy for Hoharwa Monastery – A Unique Piece of Betä Ǝsraʾel Historiography

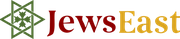

Fol. 4r: Beginning of Genesis 1; Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

Hidden under the simple description of “Old Testament (Orit)” lies a true treasure in the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. Manuscript NLi Ms. Or. 87 is much more than a simple Orit manuscript. It contains as an additional text the second original piece of Betä Ǝsraʾel historiography ever to be discovered. So far only “A Falasha Religious Dispute” published by Wolf Leslau has been known to exist. As if this was not a significant discovery on its own, the document has even more to offer. This historiographical text is a monastic genealogy for Abba Wärqe, a monk of Hoharwa – the most important Betä Ǝsraʾel monastery, located on one of the seven holy mountains of this religious group.

A full scholarly article devoted to this outstanding manuscript will appear in Aethiopica. International Journal for Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies 23, 2020.

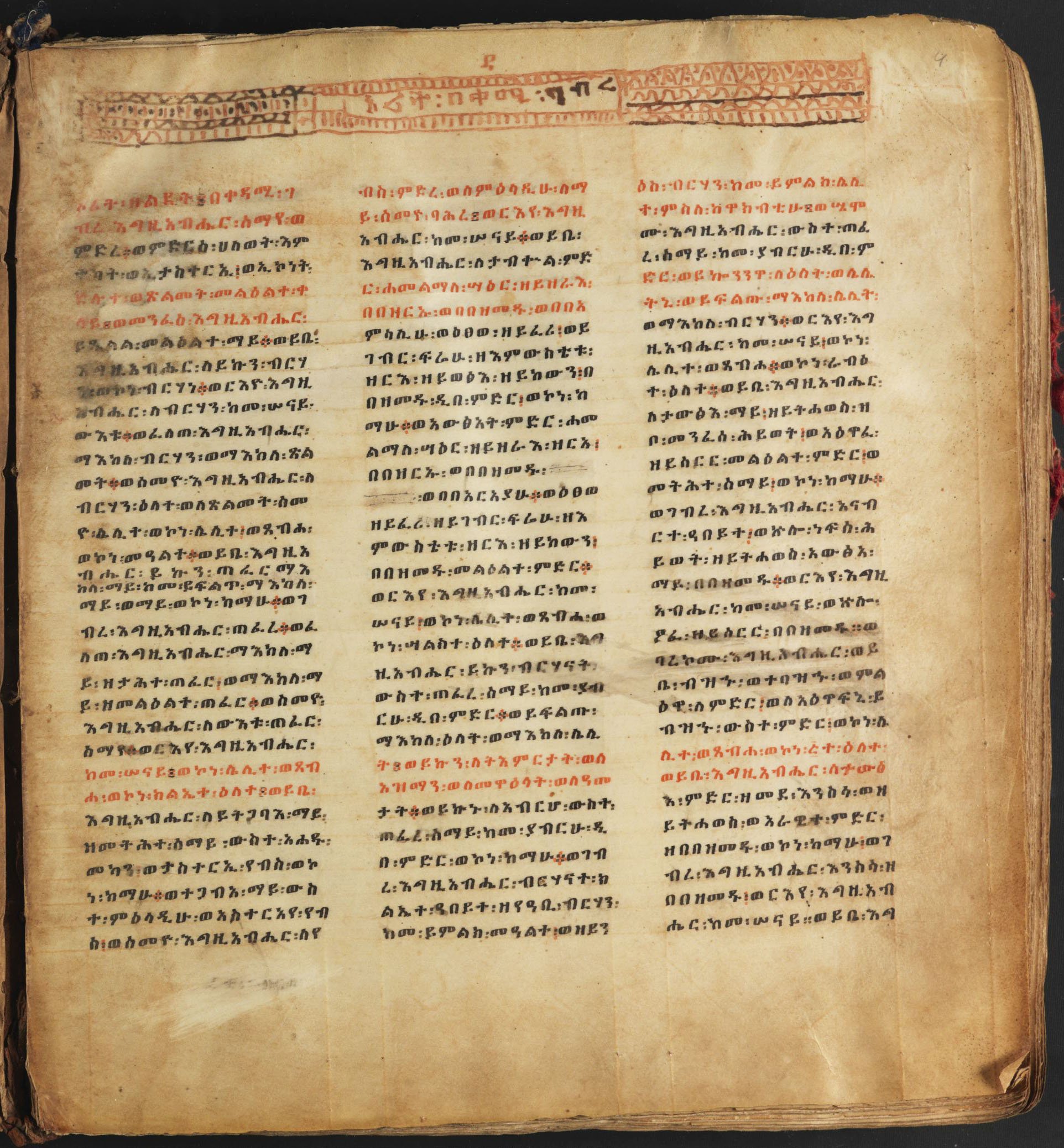

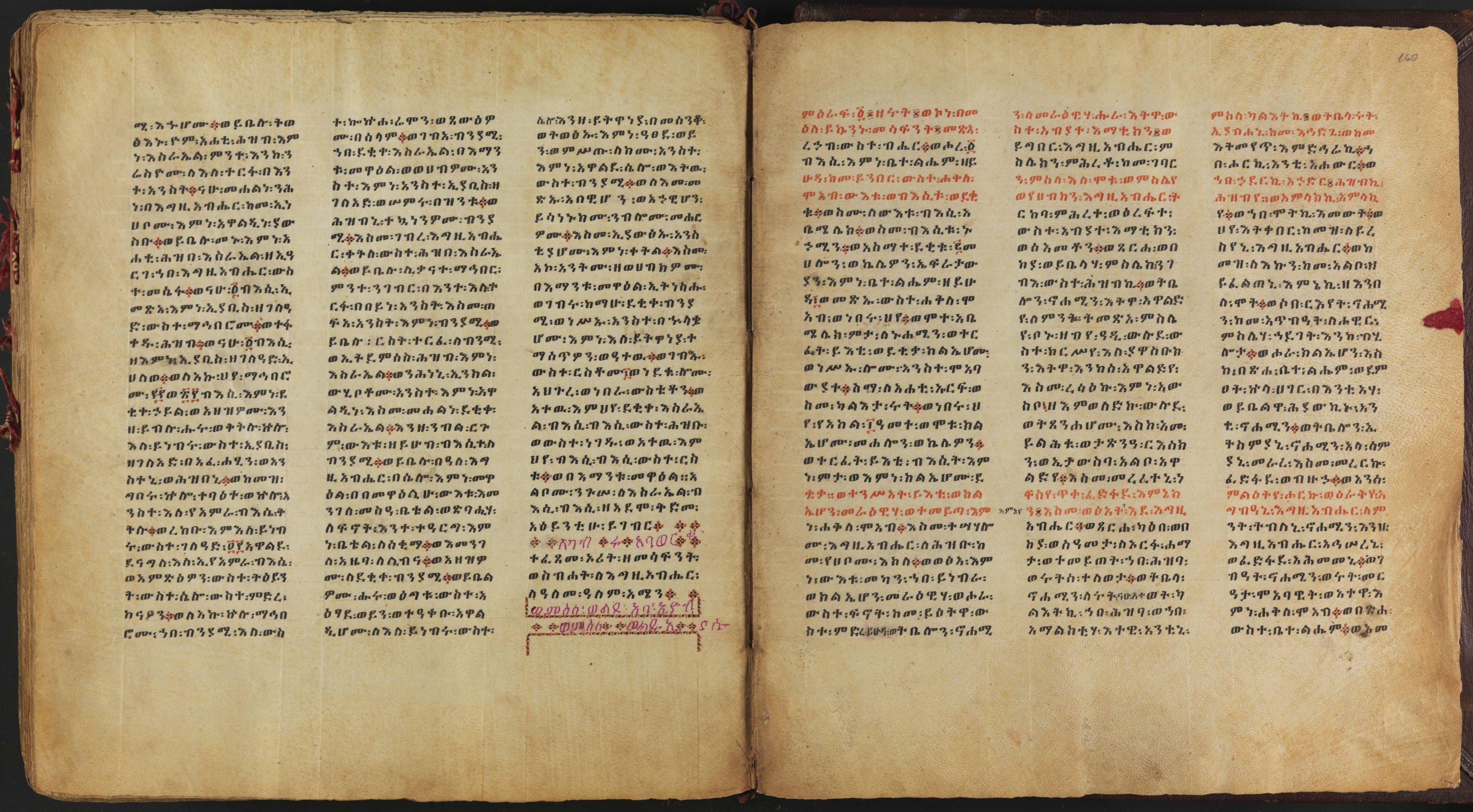

Fol. 162v/163r: End of Betä Ǝsraʾel prayer, protective prayer for Männa, genealogy of Abba Wärqe, genealogy of Abba Iyob, secret script (upper right corner); Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

Now, What Makes this Genealogy so Important?

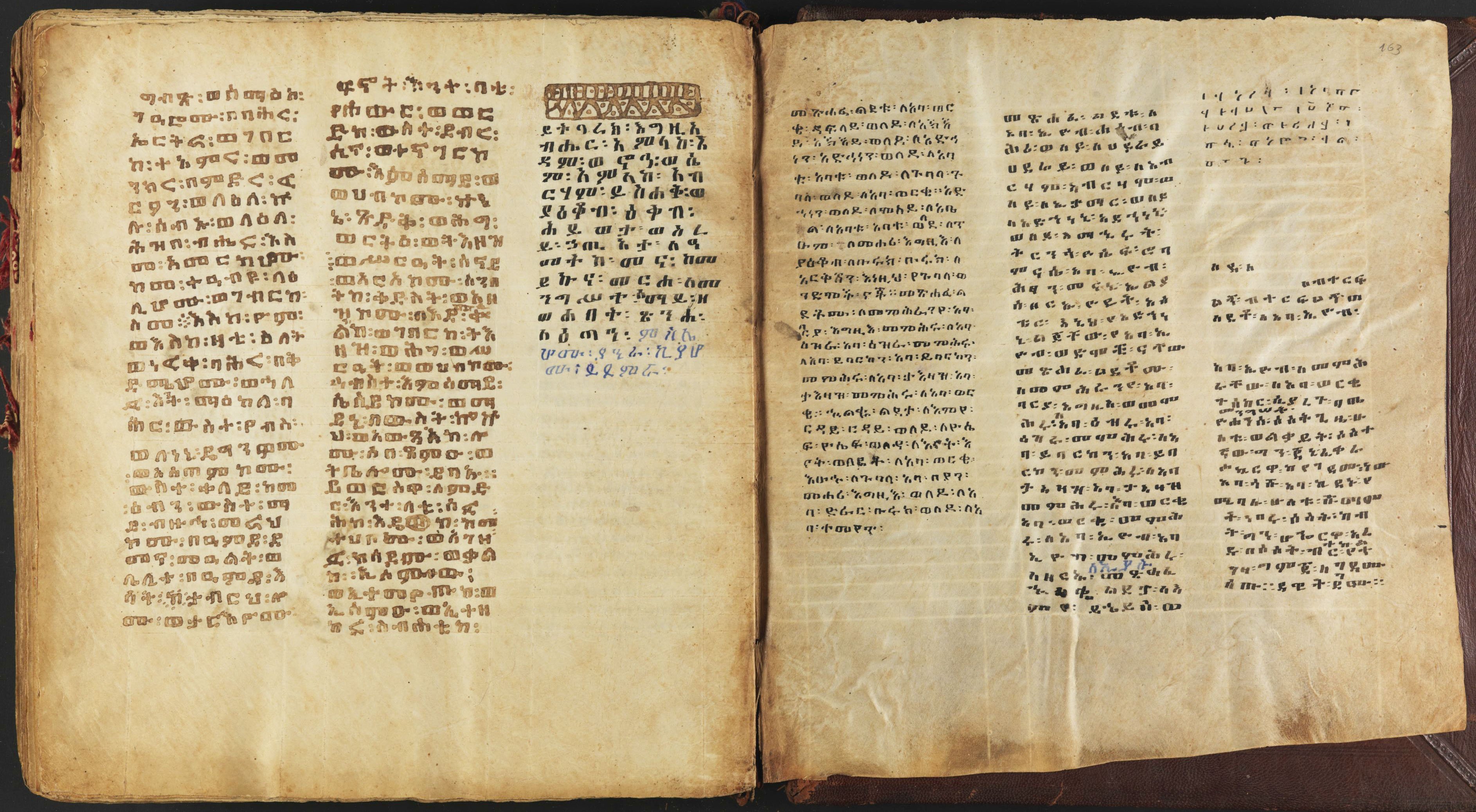

Literally everybody who has ever studied the Betä Ǝsraʾel has stressed that this religious group has not written down any of its own history, but that all the traditions have been transmitted orally. Manuscript NLi Ms. Or. 87 comes to prove that this is not completely true. It contains in truth two separate genealogies, which relate to each other. Abba Wärqe, owner of the manuscript, and author of another additional text (see below), wrote the first note, and the second was (most probably) written by his disciple Abba Iyob. While the spelling of the names differs slightly in both lists, the genealogies build upon each other, with Abba Iyob clearly being the disciple of Abba Wärqe.

Besides few names of Betä Ǝsraʾel in the commemorative notes of some manuscripts, which only reveal their names but nothing more, these monastic genealogies are an absolute novum. Abba Wärqe does not only list his spiritual genealogy but also his earthly family, his father and mother, his brother and uncle.

The list that Abba Iyob wrote finally reveals the name of their monastery, Hoharwa. His note tells us that he celebrated the täzkar, the traditional mourning ceremonies, five times for his spiritual father, even in two different monasteries. In addition, he sacrificed three cows in his honor and donated a traditional luxurious garment, showing his deep respect and veneration for his master. He further notes that this happened during the reign of King Yoḥannəs. In Ethiopian history there were four Kings by the name of Yoḥannəs but based on codicological and paleographical evidence I suspect that it was Yoḥannəs IV, who ruled in 1872-1889, giving us approximate dates for Abba Iyob’s lifetime.

Fol. 163r: Genealogy of Abba Wärqe, genealogy of Abba Iyob, secret script (upper right corner); Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

The Special Place of Monasticism in Betä Ǝsraʾel Society

The monastic tradition of the Betä Ǝsraʾel is one of the unique markers of this religious group. While in the past it was often viewed as a “substratum” of the Christian Ethiopian tradition, our research – and especially the meticulous PhD thesis of JewsEast member Bar Kribus – reveal that the Betä Ǝsraʾel monks played a much more important role for the community than Christian monks ever did. In the absence of a Patriarch or Bishops, or a centralized political leadership, it was the Beta Ǝsraʾel monks who held the position of religious authority, leading all other clerics, consecrating new priests, and leading the community. Among the Betä Ǝsraʾel monasteries, the monastery of Hoharwa was the most revered and holy one.

The importance of the monastery of Hoharwa is due to the tradition that associates it with the founder of Betä Ǝsraʾel monasticism -- Abba Ṣabra who (probably) lived in the 15th c. The legends about Abba Ṣabra are numerous and confusing. Some hold that he was a Christian and the father-confessor of none other than the Emperor Zärʾa Yaʿəqob (r. 1434-1468). He and one of the Emperor’s sons, Ṣägga Amlak, incurred the wrath of the Emperor, who was indeed a religious zealot. When Zärʾa Yaʿəqob threatened to have them executed they fled into the wilderness. Other legends claim that he was a Betä Ǝsraʾel from the Semien mountains. However, these disparate traditions all agree on the point that Abba Ṣabra and Ṣägga Amlak traveled to remote areas to avoid the Emperor’s soldiers. They arrived in Hoharwa where they spent the rest of their life. Abba Ṣabra is accredited with having established the strict purity laws of the Betä Ǝsraʾel, with teaching the Orit to the people, and finally with introducing monasticism to the community.

What do we Know about Hoharwa?

Hoharwa, which is the name for the monastery as well as the mountain on which it is located is a storied place. Its exact location has not yet been determined, but it is known to be located in the region of Ǧanfänkära, north-west of Gondär. In the past a few European travelers managed to reach it, but all recount hazardous travels and difficult journeys. Their reports also vary in some parts. The Jewish traveler Jacques Faïtlovitch writes in 1910 that “the Hoharua-mountains allow a view over the entire region all the way to Sudan”, and continues describing its rough cliffs and peaks. He further states that “the temple itself, is the most beautiful synagogue among all those of the Betä Ǝsraʾel, being constructed of massive stone walls in characteristically temple shape.”

While all accounts about Hoharwa agree that it was the most important monastery of the Betä Ǝsraʾel, they differ in giving the size of its monastic community. Some state that during the Gondärine period (1630s-1769) around 250 monks and nuns lived in Hoharwa. By the 19th c. this number had most probably declined to around 20 monks.

There is no consensus about the correct spelling of Hoharwa; even our source gives the name in two different versions. No etymology has been established so far.

The JewEast Ethiopia team, namely Bar Kribus and myself, hope to locate the monastery in the upcoming fieldtrip, October 2019.

The location of the region of Ǧanfänkära, within which the monastery of Hoharwa is located

What does the Manuscript Reveal about Abba Wärqe?

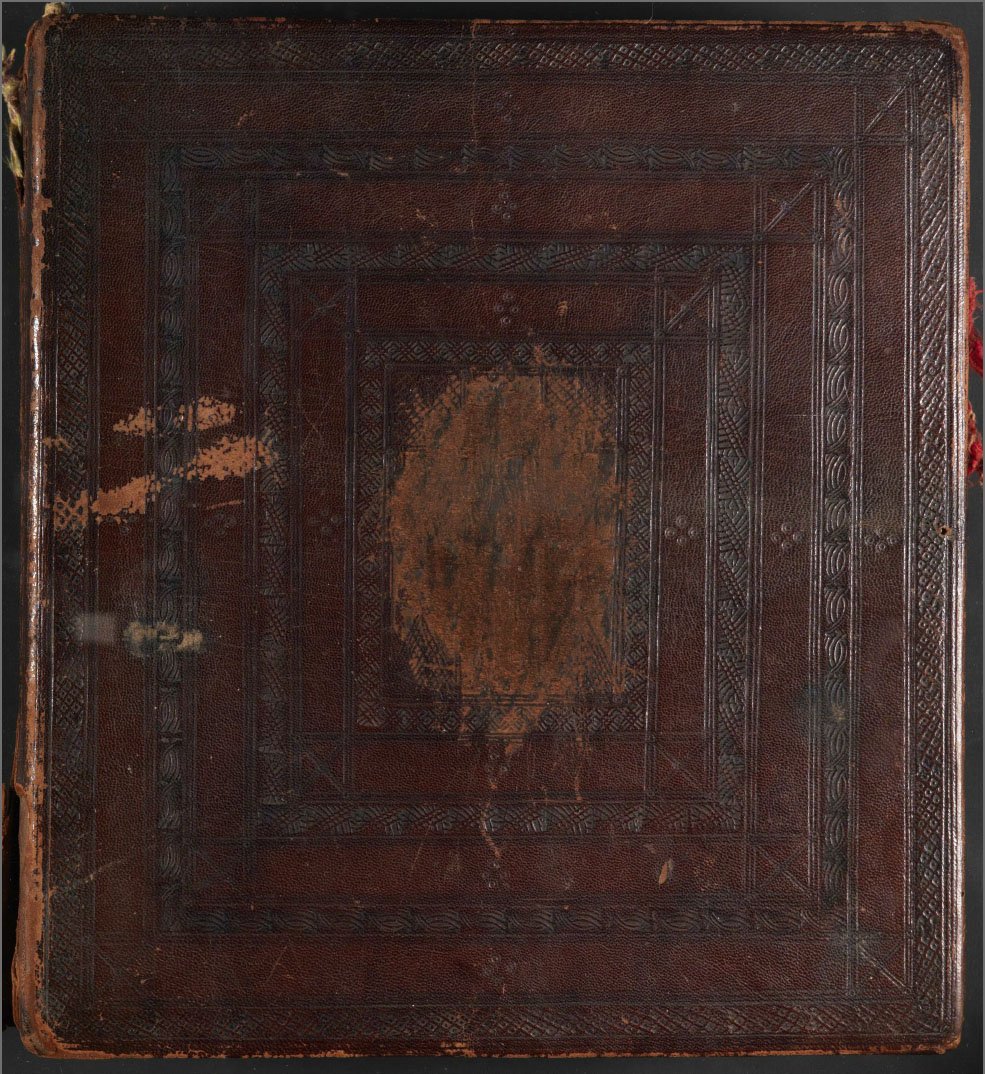

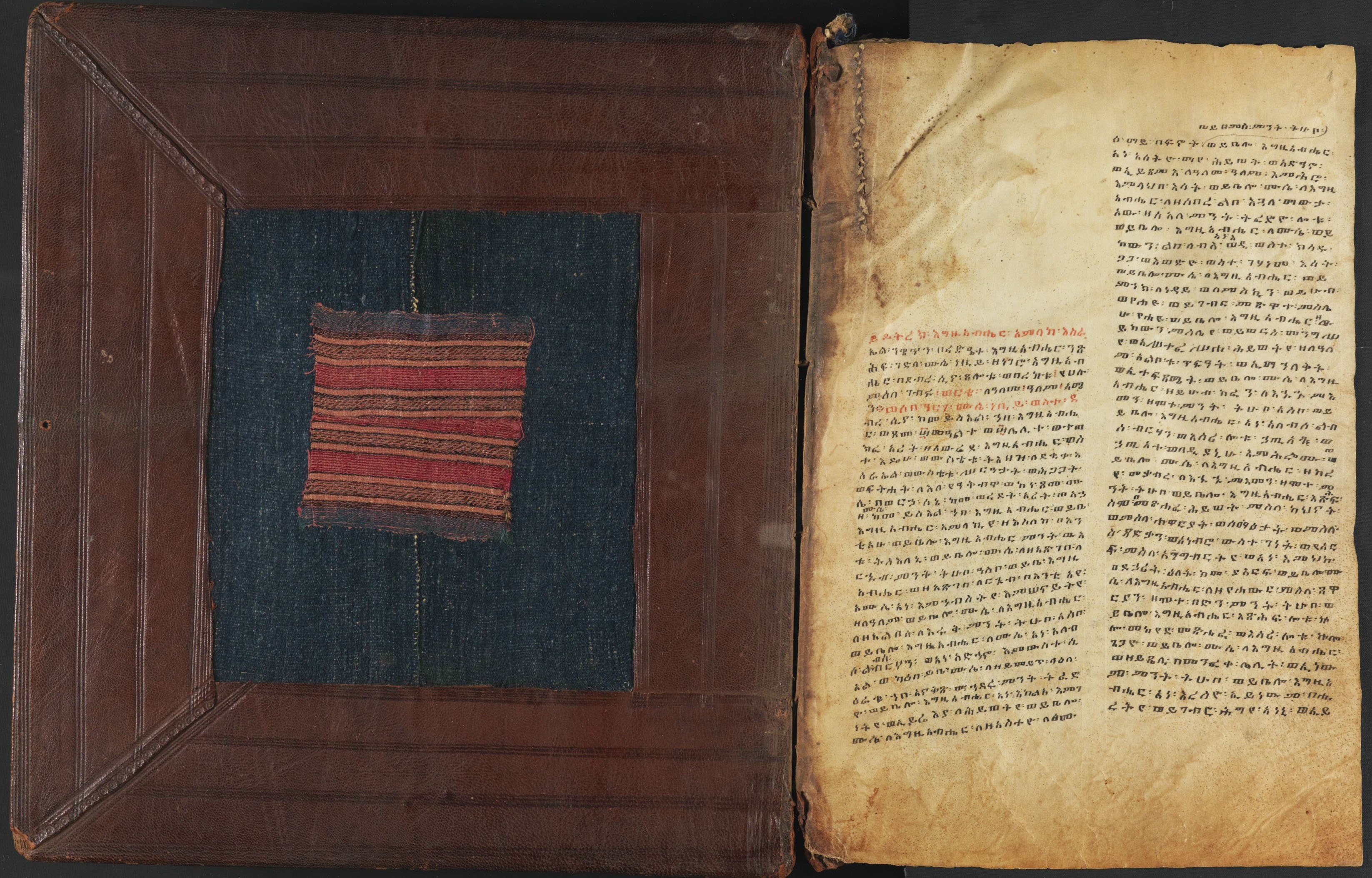

In order to answer this question, we should take a closer look at the entire codex NLi Ms. Or. 87. The manuscript contains peculiarities which mark it as an outstanding piece of Betä Ǝsraʾel material culture. It was assumedly written by a Christian scribe but commissioned by Abba Wärqe, which was common practice. While it is known that Betä Ǝsraʾel clerics knew how to write they did not reach high craftsmanship. Codex NLi Ms. Or. 87 is however a very impressive manuscript, of considerable size – roughly 34cm height and 31cm width. The codex is bound in the typical reddish-brown leather cover, embossed with ornaments. Here it is a perfect representative of the Christian Ethiopian manuscript tradition and follows all rules one would expect. However, the cross that is usually the center of these ornaments was scratched out on both covers of this codex. This is a clear indication that it was repurposed to suit a Jewish owner.

Front cover, with cross-ornament scratched off; Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

The handwriting, albeit hinting to a rather recent age, is neat and careful. The text is arranged in three columns, which is relatively uncommon for Betä Ǝsraʾel manuscripts. The main text of the codex is the Orit, which comprises the first five books of the Old Testament as well as Joshua, Judges, and Ruth. Throughout the manuscript are annotations in the margins for internal chapter headings and reading indications, most probably written by Abba Wärqe.

Fols. 159v/160r: End of the Book of Judges with supplication note for Abba Wärqe, Iyob and Iyasu, beginning of Ruth; Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

Together with the genealogies there are in total 5 additional texts all written by Betä Ǝsraʾel; one of them is a protective prayer for a woman called Männa. The longest additional text is a Nägärä Muse (The Colloquy of Moses), spread over fols. 1ra-3r and written by Abba Wärqe himself. Lastly there are two short notes in secret script which have until this moment not been fully deciphered.

This fine manuscript was not a cheap, average manuscript, and its owner must have been a learned man, who was able to write the text of the Nägärä Muse, the annotations to the Orit-text, employing secret script and finally to record and leave us with his own monastic genealogy. He was highly venerated by his disciple, who spent a lot of money to honor his memory. Therefore, I would like to speculate that he could have been the head of Hoharwa monastery at some point in his life, which means probably in the early 19th c.

Inner front cover/Fol. 1r: Careful ornamentation on the tooled leather cover of the turn-ins, beginning of Nägärä Muse; Jerusalem - The National Library of Israel, Ms.Or. 87

What can we Learn from the Genealogies?

This document of Betä Ǝsraʾel material culture sheds light on the history and monastic practices of the Hoharwa monastery – the most important Betä Ǝsraʾel monastery, and indicates that its monks could purchase and modify manuscripts prepared by Christian scribes and craftsmen. By comparing this genealogy with monastic genealogies preserved in the Betä Ǝsraʾel oral tradition, it may be possible to shed further light on the individuals and on the events mentioned therein. The codex further demonstrates the importance of searching through Betä Ǝsraʾel manuscripts for marginal notes and additional texts, which is a task that our team plans to carry out in the future.

Our work of locating the remains of the Betä Ǝsraʾel monastic centers often reminds us of a treasure hunt. There are neither tangible traces nor written documents that could lead us to the sites. We fully rely on oral information, most of which were recorded decades after the Betä Ǝsraʾel left Ethiopia. The monastic genealogies of the monks Abba Wärqe, Abba Iyob and Abba Iyasu of Hoharwa monastery are an unparalleled discovery: they add new information about this important place, which our team will hopefully be able to document soon in more detail.

Follow up report, June 2020.

As stated above the JewsEast team tried to reach Hoharwa in our October 2019 field trip. It was not an easy field season, there was political unrest in some of the regions we planned to visit. In addition the rainy season of that year was unexpectedly and untypically long, and heavy rains made several roads impassable.

Impassable roads, Mt. Anqwadib in the background

We tried our best to reach Hoharwa, but have to put our names on the list of scholars who were not able to do so. We came as close as Ayeqwa, a place mentioned by Faitlovich in his travel reports, where we documented an abandoned Betä Ǝsraʾel cemetery and conducted some interviews.

The only mountain in the area which seemed to fit the description “the Hoharua-mountains allow a view over the entire region all the way to Sudan” (Faïtlovitch 1910, 88) is the impressive mountain called Anqwadib, which was also described and mapped by the German traveler Eduard Rüppell in 1840, along with the nearby mountain Kərwa. However, we have reason to believe that this is not the location of the monastery of Hoharwa.

Photo with both mountains: Anqwadib on the right, Kərwa to the left

We hope for more favorable political and climatic conditions in the future to finally reach this important monastic center. More details will be published in Aethiopica. International Journal for Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies 23, 2020