Two Stories about Jews in Armenian: Part 2

This article is the long-promised Part 2 of an entry presented some months ago, dedicated to two sources about Jews preserved in Armenian. The first, dedicated to the Story of the Icon of Beirut, can be read here and will be referred to occasionally in this Part 2 as well.

The Text

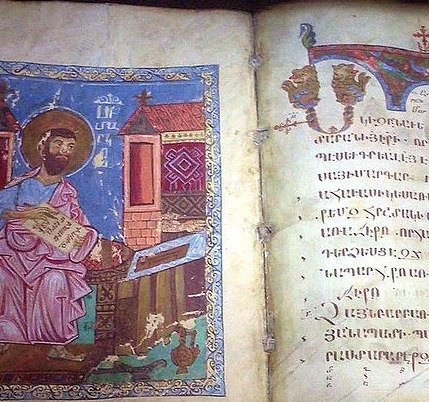

It was following the traces of the Icon of Beirut that another tale transmitted in some of the same manuscripts and involving a Jewish woman came to my attention. It is entitled De episcopo qui cum Hebraea fornicabatur/"On the Bishop who Fornicated with a Jewish Woman" (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca 1442n). Its précis appears in that wonderful scholarly tool that is the Repertoire of Byzantine “Beneficial Tales” prepared by John Wortley, where it is numbered W008. Thus far, I have not come across extensive discussions of this story in the secondary literature, beyond its publication by M. Canard in 1966 (“Trois groupes de récits édifiants byzantins”, Byzantion 36 (1966): 5-25, text on pp. 24-5). BHG signals only three Greek manuscripts with the text. At this stage of research I have identified two Armenian manuscripts but there are certainly more.

The Contents

This tale has not been subject to detailed studies. Compared to the Greek version, the Armenian has some differences, but the gist of the story is the following. A bishop lived in the sin of porneia. His lover was a pious and God-loving Jewish woman whom he tried to baptize but to no avail. However, at the bishop’s continuous insistence, the woman finally decided to attend Sunday service at the church where her lover would officiate. As he ascended the altar and started the mass, an “angel of light” appeared and tied him to a column, performing the liturgy in the bishop’s stead. Moreover, at the moment of the “raising of the Holy Mystery”, the woman saw a young boy brighter than the sun, from whom the angel cut pieces and distributed to the faithful. At the end of the Communion, the boy, fully intact, rose to heaven. This vision was seen only by the Jewish woman, the text specifies. With tears in her eyes, the woman told the story to the bishop later that evening, begging him to baptize her. She, then, joined a monastery and convinced her former lover to repent his own sins, too. Upon fulfilling her wishes, the bishop left his high position and went to the Holy City where he lived as an anonymous ascetic. The woman died in holiness in her monastery, while the bishop lived three years longer, performing numerous miracles during this time.

Possible Functions of the Texts

There is much to be said about this short but colorful tale. The text has several intriguing features which must have influenced the way it was read, perceived and utilized for various “edifying” purposes. Some of its salient lessons are rather obvious even from a first, superficial reading. Already Wortley’s clear cross-references to similar texts, as well as Canart’s notes to the Greek edition, emphasize one important topos in this text: the sacredness of the Eucharist and the purity of the celebrant as a necessary condition for its validity. This is an important message transmitted by the text that must have made it a most useful tool for homiletic/paraenetic purposes, aimed at the clergy. In fact, other short narratives with a similar structure (cross-referenced in Wortley’s index) also feature a sinful priest or a bishop, who is prevented from celebrating a sacrament on account of his sinful behavior. However, the inter-religious context of this and other such tales are not to be neglected.

In our tale, the pious Jewish woman embodies several characteristics that are typically ascribed to the female religious “Other”. Like in medieval European sources on Jewish women, also in this story the woman (or women in general) appears as a perfect potential convert, as opposed to men who are often depicted as diffident and hard to convince. In fact, in the story of the Icon of Beirut, Jewish men appear to be belligerent and even violent towards Christianity and its symbols, something entirely absent in the Story of the Jewish Woman. In the tradition of the Apophthegmata Patrum or the so-called “Edifying Tales”, we find other similar stories where the positive actors are women belonging to a different religious community, the latter not necessarily restricted to the Jews. Thus, there is a similar tale where the role of the Jewess is taken by a Saracen girl (BHG 1317g; W007). This may mean that at least in Late Antiquity the theme was popular and reused with slightly different variants. It transmitted at least two clear messages: exalting the sacredness of the Eucharist and calling for purity of the one officiating; and using the Eucharistic miracle for the conversion, perhaps especially of women, of members of other religious communities.

Other Interesting Features

Despite the topos of malleability of women and potential facility of converting them as opposed to men, the Jewish woman in our tale is hardly a passive recipient of a new religious message and an uncritical convert. On the contrary, she is the one taking decisions and not only for her own actions. She converts out of her own free will (rather than forced persuasion), after which it is her that convinces her lover to leave his sinful ways and follow that path of “true” holiness.

Reading this tale another detail comes as a surprise. The text presumes that its readers (or hearers) would find nothing unexpected or shocking for a Jewish woman to be present in the church during the entire Eucharistic service. Whether such an attitude is simply another rhetorical trope or expresses an unexpected openness of religious rites (despite abundant evidence to the contrary), provides us with further salient points for reflection.

The Manuscript Context

In the Greek tradition this text is included in some manuscripts of Pratum Spirituale. Some of the tales from Pratum do appear in Armenian collections of Apophthegmata Patrum (or Paterikon mss), but the published version does not include the story On the Bishop and the Jewish Woman. Two manuscripts have been thus far identified with this text: M3260 and V203/985, both collections of homilies. It is not easy to identify the text in manuscript catalogues because of its anonymity, not to say that not all catalogues of even major manuscript holdings have an index. It will thus require time dedicated to catalogue-searching before a fuller view of the manuscript tradition can be achieved and a critical or any kind of scholarly text established. Moreover, the “establishment of a text” itself will be more complicated here, given the usual problems of editing such semi-oral traditions, with numerous reworkings and “exuberance of variants”.

The Original Language of the Texts

A first reading of Armenian vs Greek texts indicates that the Armenian is a free, abbreviated rendering of the Greek version. But is it actually based on a Greek Vorlage? Like in the case of the Icon of Beirut, toponyms compel us to question a presumed Greek original. In fact, the Greek text places the story in a puzzling “city of Ethiopia near Gaza”, while in the Armenian version the action takes place in the “city of Msr”/ի քաղաքին Մսրայ (i.e. Egypt). The use of the Arabic toponym Msr as opposed to Egypt already hints at the possibility that the Armenian may have been translated from Syriac or Arabic. Both these hypotheses need further research before they can be confirmed.

More Questions for Future Research

A future analysis of the tale on the Bishop and the Jewish Woman must explore nuances within general attitudes towards the Jewish “Other” by exploring the differences of approach to Jewish men vs women. The two texts considered in these two entries employ certain stereotypes: while the Jewish men from the Icon of Beirut story are prone to violence (against the icon and by implication Christ) there is nothing to be reproached in the Jewish woman’s behavior before or after her conversion. While in some anti-Jewish texts Jewish women are presented as docile potential converts, here the woman is the one taking action on her own initiative and the decision to convert is not imposed on her.

In the Icon of Beirut and the tale On the Bishop and the Jewish Woman two types of conversion are presented: one communal and one individual. In both cases, however, the conversions are not the result of sophisticated theological argumentations. These texts emphasize the importance of liturgy and miracles, thus, the praxis of religion, as opposed to more formal Adversus Judaeos sermons or Dialogues (altercatio) whether fictitious (mostly) or real between Christians and Jews. The tale On the Bishop and the Jewish Woman affirms the reality of the Divine presence at the Liturgy (just like the Icon of Beirut does for icons), but also turns on its head the very old argument brought against Christians by pagans – Christians eating children – a caricature of the Eucharistic service. In fact, the woman sees Christians “eating” a child without it causing any harm to the “celestial” boy. We have to conclude, then, that both of these texts, and many others that betray real or imagined Jewish-Christian confrontation serve more than one function. Exploring those in different cultural and linguistic contexts, especially through a comparative approach, is something with which JewsEast hopes to contribute to the general scholarly community.